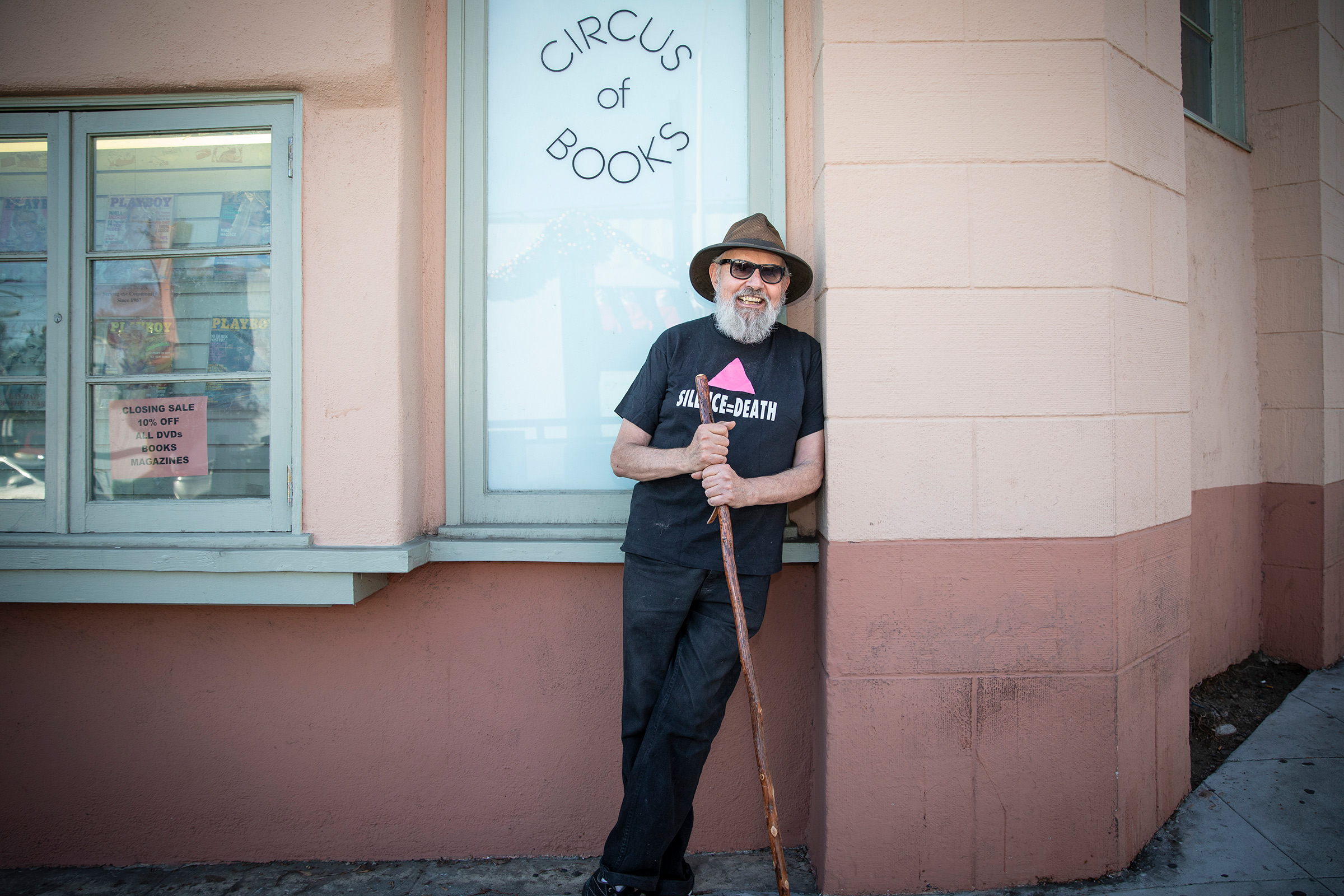

Wendell Jones

“It was as if the developers said, ‘How dare you have a city that’s based on the pursuit of happiness.’”

West Hollywood is one of the few cities in the nation that was built specifically so we could have rent control, but Cityhood came about not just because we wanted rent control. When we fought for Cityhood, we were projecting our best selves onto making a city. We were imagining that there really could be a better world.

If you go back to the Bill of Rights, it talked about the fundamental rights that we all have as individuals, and they include life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness—and it didn’t mean just walking around smiling on Prozac. It meant: to work at the job that you want to, to love the person that you really care about the most in the world. The Coalition for Economic Survival (CES) understood that. They were fighting for better wages for people who were working in jobs. They were trying to get rent control to keep people in their homes.

I was living and working in Venice in the mid–1980s—doing tenant counseling at one of the L.A. area clinics my friends and I started when we attended the National Lawyers Guild Peoples College of Law. I had seniors from West Hollywood coming to the clinic saying, “My landlord just tripled my rent. I’ve been there all my life; what am I going to do? I’m on a fixed income.” So once West Hollywood Cityhood got on the ballot, I got involved in the campaign. The coalition for Cityhood was primarily gay renters, senior citizen renters, and younger renters.

Going door-to-door to speak with voters about Cityhood was fascinating because you could see people wanted it. The renters wanted Cityhood because of rent control. The gay men supported it because they were being abused by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and didn’t have the right to marriage; we could be fired at any time if someone discovered we were gay. We were living terrifying lives, and the idea of a city was like magic—that you could be secure, and you could have a city that gave you the right to domestic partnership, even before it was a big thing in the state. I think the gay homeowners pushed Cityhood’s victory over the tipping point.

In 1987 I decided to move to West Hollywood. I had gotten very involved in AIDS activism with ACTUP/LA [AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power], and the group was based here because unlike the Los Angeles Police Department, the Sheriff’s Department [contracted to police West Hollywood] left us alone—basically because the City Council told them to.

The other reason for my move was because I wanted to work with the CES, and I ended up coordinating their Wednesday night Tenants’ Rights Clinics in Plummer Park. One of the things I’m most proud of in the City is that they have kept that clinic there, providing one or two lawyers, twice a week, for, what, over thirty years.

I’ve gotten so much from doing the work with CES. It’s a total joy. Some of the best friends I’ve met have been through this work. There were old Commie Jews—people like Elizabeth Burns, who used to work at the CES office doing the phones. She was a character. She loved gay people, and I loved Elizabeth.

I think the most important ingredient of our city’s success has been our ability through CES to organize, to back City Council people who would really represent our interests, and to keep track of them. We’ve had chats with them. We’ve had visits with them. We’ve had meals with them.

It is important to understand that back in the 1980s and 1990s, so many people were dying of AIDS. For example, before Cityhood, if you had AIDS and didn’t have money and you lived in West Hollywood, you got sent to what was called Los Angeles County General Hospital [now known as Los Angeles General Medical Center]. But they had no AIDS ward, so people who had AIDS were being put in wheelchairs and left to die in the hallways. This was craziness, and ACT UP started a big push to get an L.A. County AIDS ward opened. The way ACT UP was able to congregate and organize all happened out of Plummer Park in West Hollywood. It could not have happened in another city in the same way. We had a city that backed us up. We had a place to do it. Having a city that lets us meet somewhere helped our work to get the AIDS ward and get more HIV drugs legalized, which have kept people alive. That was very powerful.

The other thing that really was amazing to me as a gay activist in West Hollywood was the Assembly Bill 101 demonstrations in 1991 [against Governor Pete Wilson’s veto to ban discrimination in the workplace]. Because we had all these gay people on the City Council, they told the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department to let us demonstrate in the streets. The demonstrations lasted for weeks. There were some days I would be in my apartment over Circus of Books and I’d be working, and all of a sudden, I’d hear this noise. There would be this screaming, and horns honking, and I would run down to the street and see people stretched out from La Brea Avenue all the way to La Cienega Boulevard at the other end of the City, yelling and marching. A week later, there’s still thousands of people running down the street screaming. That was beyond anything I could imagine.

As the years went on, seeing my friends dying from AIDS, I said to myself, “What do you want to do with your life?” I realized if I could just live for a little while longer, I would like to make some art; I would like to tell some stories, write some plays. So I started working as a performance artist. I did some one-man shows. I cowrote a musical called AIDS! The Musical! That was incredibly fulfilling. I was able to do my art because I lived in an affordable apartment because of West Hollywood’s rent control law.

In 1995, the rich developers decided to strike back at the utopia we built in West Hollywood. They got a state law passed called the Costa-Hawkins Rental [Housing] Act that said if you move out of your rent-controlled unit, the landlord can raise the rent as high as they want. After the law passed, we probably at least doubled the number of people that came to the CES tenants clinic on Wednesday nights—from, like, ten people a week to twenty, thirty people: Latinos; immigrant families; senior gays; people with AIDS who have been fine and stable for a long time and now they’re getting sick, and their landlords think they can make a move on them and get them out. It was as if the developers said, “How dare you have a city that’s based on the pursuit of happiness, on old people, on gay people living decently?” Costa-Hawkins put a target on the back of any elderly renter who had been living for ten, twenty, or thirty years in their West Hollywood apartment. If I had moved, instead of a $750 studio that I have right now, it would have become a $2,000 studio for a trust fund kid. I didn’t anticipate Costa-Hawkins, and unless we get rid of it, eventually there will be no affordable housing except for the new affordable housing that is being built now. But that’s just a tiny portion of West Hollywood’s housing.

I love West Hollywood—I still can walk down the street, smile at people, and enjoy it. If I go to the bakery shop, I know the people there, and they know me. This creates a feeling of community and interconnectedness that makes a person more willing to help others.

I think what other people can learn from West Hollywood is that you’ve got to make a place livable. You have to have trees. You have to have parks. You have to have art. You have to have International Women’s Days. You have to have LGBT marches. You have to have stuff for the seniors. You have to think of a city as a community that needs to be nurtured and taken care of, and that the City shouldn’t just wait for people to come out and do it, but should be helping to provide the seed money, the buildings, the inspiration to do these things.

I don’t think there’s another city in the nation that has consistently supported the rights of women, LGBT people, and people from lower classes to thrive and reach their full potential. You see it all over the City. You go to Plummer Park, and you can see seniors taking tai chi classes out of Fiesta Hall. As a senior citizen in West Hollywood, I get a bus pass for $18 for two months. So what that is saying is seniors are valuable, and we’re not just going to let senior citizens drift off the map. If you’re a senior, and you can’t afford food, you can go get lunch in Plummer Park every day of the week. Most cities have some version of that, but it’s done here in a much, much bigger scale.

It doesn’t matter to me if there’s a gay majority on the West Hollywood City Council. If the gay majority was all from the Republican Log Cabin club, what would that mean? I want people on the City Council who support love. And who support old people. And who support children. And who support housing. And who support art. And who have a vision for a multiclass—where people who wait on us at the restaurants and clean up after us in the hotels and on the streets are part of the City. I’m proud of the City, and I’m proud of the other people who have worked together to build it. I think we’ve done a better job than any other city that I can think of, of really providing opportunity for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. I think West Hollywood is a model of what cities could be. I’m hoping that as things get bad in other places, people elsewhere will see our West Hollywood model. That’s my hope.