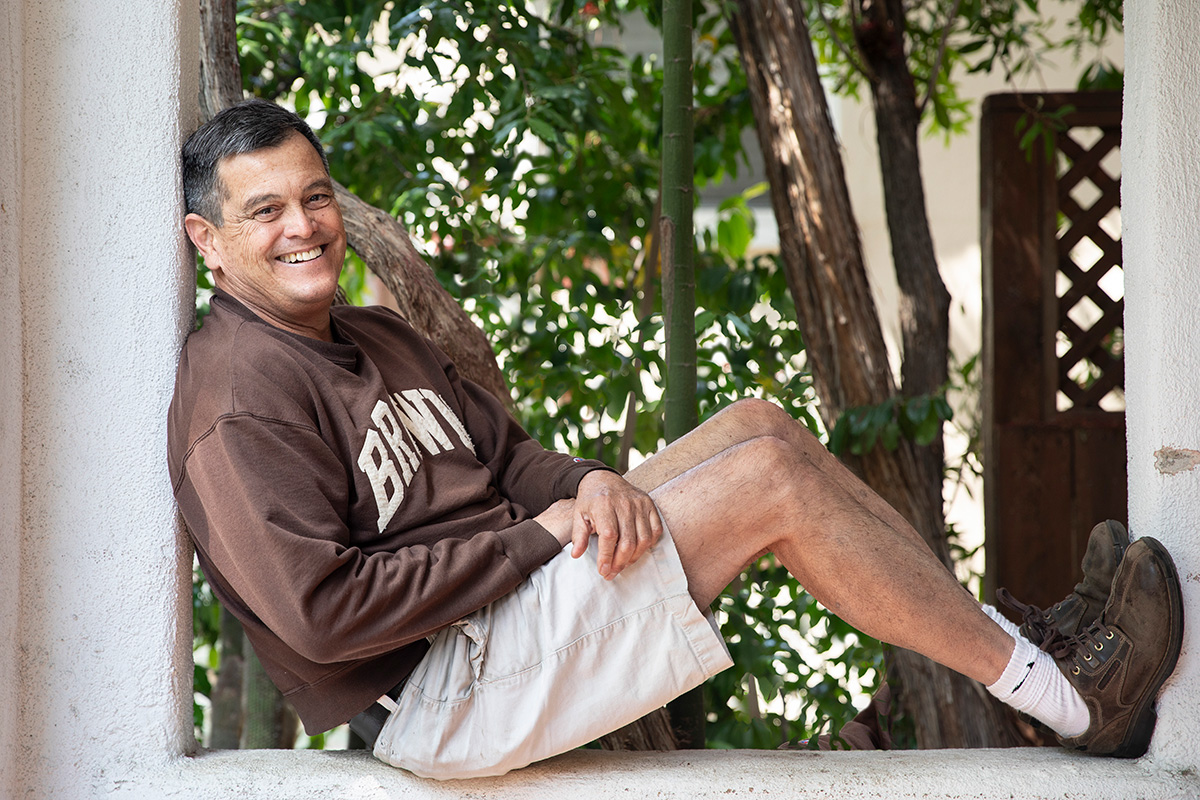

Steve Martin

“I got recruited into the Cityhood campaign at the 24 Hour Fitness gym, while I was on the Lifecycle machine.”

I was coming out as gay as an undergraduate at UCLA, and I never realized West Hollywood even existed, and then some of my friends gave me the coordinates, and I drove by one day. My jaw dropped. I just wandered around to watch people because I was just so dumbstruck that everybody seemed so normal and everybody was just having a good time, and they were so nonchalant about it. I’d never even imagined a place where you would see that many gay people wandering around as if it were the most normal thing in the world.

I moved to West Hollywood in 1979. It was a big culture shock, but I dove into life there and embraced it with gusto. You could just meet people by crossing the street or at Pavilions [supermarket]. I had to stop buying ice cream because it never made it home not melted. It was just a really fun time. And then AIDS hit.

In those days, if you were a guy in his twenties or thirties spending time in West Hollywood, you were presumed to be gay. It was nice because you didn’t have to apologize for it, you didn’t have to explain it. It was a liberating feeling, and people flocked here from all over the United States to go through that experience. If a closeted gay man told his family he was moving to San Francisco, they assumed he was gay. But if a gay man told his family he was moving to West Hollywood, you didn’t have to come out to them because everybody was moving to the L.A. area then—actors, models, waiters, porn stars, and creative people. There were people living here who were blacklisted in the McCarthy era, and straight women who felt safe because there were so many gay men walking their dogs at night, and lots of Jewish senior citizens who came after World War II and were Socialists or Communists.

I remember reading about the Cityhood campaign in Frontiers [a gay publication at the time], and it was exciting because it was clearly going to be an opportunity to create an enclave of gay power. At some point during the campaign, I got a thirty percent rent increase and suddenly I was a true believer in Cityhood. I got recruited into the Cityhood campaign at the 24 Hour Fitness gym, while I was on the Lifecycle machine. I’d dislocated my clavicle and couldn’t do my normal workout, so I was sitting on the Lifecycle when my friend Howard Armistead, a Democratic activist, sees me and gets on the Lifecycle next to me. I’m a captive audience. Just to get him to shut up, I agreed to go to this meeting that was something about Cityhood at the West Hollywood Democratic Club—a new club he founded. I figured the Coalition for Economic Survival’s (CES’s) campaign already had its people, so I got involved with others working for Cityhood. It was easy to be drawn to Steve Schulte [a candidate for City Council on the ballot], and then I met Joyce Hundal [another candidate], who taught me a lot about West Hollywood. I had joined Stonewall by then too. The two Democratic gay clubs—the Harvey Milk Democratic Club and the Stonewall Democratic Club—were the other main groups campaigning for Cityhood besides CES. Stonewall was the more conservative of the two. Everybody in the Democratic circles knew if you were from Harvey Milk, there was no mistaking you were gay and progressive. But back in the 1980s, many people didn’t know what Stonewall was.

During the campaign, it was like being at Woodstock. I don’t think I was in a campaign quite like it ever again. Everybody was knocking on doors, talking to voters. Other than a few condo buildings—nobody had security buildings back then—you would walk into any apartment building, and people welcomed you and wanted to talk about the issues. Almost all the voters seemed to be pro-Cityhood. Occasionally, you’d run into a homeowner who wasn’t, or someone who didn’t support the kind of strong Santa Monica kind of rent control that was obvious we’d have if Cityhood passed.

Along with voting on Cityhood, we had to vote for five candidates for City Council. The cast of characters was great. There was a senior—Mary Beavers—who wanted to put showers on Santa Monica Boulevard for the homeless, and Bill Larkin, who was a former DA, who lived above what was then the Blue Parrot—now Revolver—where a DJ from the new radio station KROQ would play cutting-edge music on the weekends. There were CES members Ruth Williams and Norman Chramoff, who ran on a dissent CES slate to its official slate of five candidates. Then there were candidates like Bud Siegel, Jeanne Dobrin, and Joyce Hundal—the old guard who had established themselves as a political beachhead with Los Angeles County Supervisor Ed Edelman. They seemed a bit bewildered because they had never seen this sort of activism here before, but CES people had been tilling these fields for years. I didn’t realize the power CES had until after the election and four of their five candidates won.

After Cityhood, I stayed involved with Stonewall and the West Hollywood Democratic Club [now the West Hollywood Beverly Hills Democratic Club]. Two years later, I remember walking door-to-door with Councilmember Steve Schulte when he was running for reelection, and it was hilarious, because you would knock on doors of gay men, they would open the door and see Steve and their jaws would drop because he was known as a former gay model. Steve would say, “Don’t forget to vote for me,” and these guys were so tongue-tied, they could never get anything out.

I said, “Steve, you didn’t even tell him your name,” and he goes, “I don’t need to tell them my name,” which actually was true. It was so, so funny and Steve did win re-election. But aside from those things, I didn’t really get involved in City stuff until 1988.

I had an awakening when the City proposed putting a $25 million civic center in West Hollywood Park. I mean, West Hollywood Park was a crappy park. All of our parks have suffered from lack of improvements by the county, but knocking out the pool and replacing the green space with rooftop gardens and balconies seemed like a bad idea. Steve Schulte was the only councilmember opposing the proposal, and he put together a committee of real disparate people to circulate petitions to get a measure on the ballot to stop the plan from going forward. We were collecting signatures, and the long and short of it was that shortly before the signatures had to be turned into the West Hollywood City Clerk, our efforts started to lag. I phoned a couple of people to collect more signatures and it ended up qualifying for the ballot. Suddenly, I was like this celebrity. I was out there every weekend campaigning for the measure and became the spokesperson for the Save Our Parks campaign. The initiative was on the City ballot in November 1989, it won, and we saved the park.

I decided to run for City Council in 1990, but I lost. After that, Councilmember Steve Schulte appointed me to the Rent Stabilization Commission. I was taken under the wing of Commissioner Doug Routh, a leader in CES. Doug understated leadership skills and managed to get that commission through a lot of bitter issues with consensus and grace.

From 1990 to 1992, I was president of the Stonewall Democratic Club. Back then, the club was doing real grassroots work on AIDS, and taking on Los Angeles Police Chief Daryl Gates and the Sheriff’s Department. I did security a couple of nights at the Queer Village on Santa Monica Boulevard and Crescent Heights when there were hunger fasts to get Governor Wilson to sign Assembly Bill 101. I was there one afternoon with John Duran and Morris Kight, and we were expecting an announcement that Wilson had signed the bill. Then we heard that he had vetoed it. I remember Morris saying, “Activate your phone trees.” We took a 45-minute break to call our lists, and then people started pouring out on the streets. All of a sudden, people were pouring out of bars, the 24 Hour Fitness gym, and the stores. That was the start of huge demonstrations that lasted every night for about three weeks.

I ran again for City Council in 1994. I had made my bones on being pro-park and pro-tenant. I was against turning housing into hotels, which City Council started doing around then for the revenue. I got CES’s endorsement this time and I won. When I got on the City Council, it was the Clinton recession, and we had to make cuts to social services. As a councilmember, I wanted to make the City more accountable and to work on economic development. Nobody besides John Heilman wanted to be on the council’s Budget Subcommittee, so I asked to be appointed. I enjoyed working with John. We both realized that most of the things that he wanted to do and most of the things that I wanted to do were not mutually exclusive. If we didn’t agree, we just presented our ideas to the City Council and let them decide.

For years, the City talked about taking over the Santa Monica Boulevard median strip from state-owned Caltrans [California Department of Transportation] because the state left it a mess. I was very lucky in that I knew Governor Gray Davis and his wife, Sharon, for a long time, and when I heard that the state had infrastructure money to spend, I turned to them. I knew they were West Hollywood residents and when I ran into Sharon at the Pavilions grocery store at eleven o’clock at night, we talked about this. She went home and told Gray about my ideas for the median strip. I mean, this is just a small town and because I had that relationship, the City was able to get funding to rip up the median strip, replace the sewers, widen the sidewalks, and relandscape. West Hollywood only had to come up with like $3 or $4 million because we got state funding. That project proved to developers that West Hollywood was willing to invest in itself—and just because we were gay and progressive, we weren’t flaky.

I also thought we needed to redevelop the eastside of town and get rid of prostitution there, so I spent a year talking to neighborhood leaders to turn the opponents of redevelopment into supporters. That is how we got the Gateway Project at Santa Monica Boulevard and La Brea. It started generating $4 to $5 million a year for the City, and boom, all of a sudden West Hollywood was on the map. I also created Kings Road Park in the middle of the City, which was controversial because Councilmembers John Heilman and Abbe Land wanted affordable housing to go there, but the neighbors wanted a park. People use that park every day now. I’m very proud that we could redo it. I’m also proud that I figured out ways to refurbish the West Hollywood Park pool and expand pool hours from ten weeks to fifty weeks.

One thing I learned on the City Council was that you never know who the bearer of wisdom could be, because every once in a while, even crabby old activists have good ideas—like Bud Kopps, God bless him. He’d come down to every council meeting wearing a captain’s hat and speak with a big booming voice. He’d just find reasons to criticize the City Council for everything. As a councilmember, you’re sitting up there and you’re trying not to make faces, even though a lot of what he’s saying isn’t true. One day he was just babbling and then he changed the subject and said, “The church on the corner of San Vicente and Cynthia is for sale and wouldn’t that be a great place for a fire station?” We’d spent three years trying to find a spot for a fire station and that was the best suggestion I’d heard so far. That’s where the fire station went. Ninety-nine percent of the time he was wrong, but sometimes that one right thing created a really good thing.

While I was on a trip to Washington D.C. with gay elected officials from around the country, I realized we do live in a progressive gay Camelot where we can do things that people can’t do everywhere. Sometimes, though, West Hollywood struggles with the idea that we’re still relevant. The mere fact we exist makes us relevant. For example, in 2004, when California Governor Gavin Newsom started issuing marriage licenses, it was a little disconcerting to me in that the City chose to turn the gay marriage thing into a City circus where even nonresidents could get married here. I know the City was trying to say, “Oh, we’re providing a safe place for people to get married,” but initially what we wanted in marriage equality was for people to be able to get married in their own community, whether it was Van Nuys or Alhambra or wherever.

Instead, what West Hollywood said was “Come here, get married by a councilmember.” To a lot of activists like me, that seemed like an exploitation of people’s euphoria.

I was on the City Council for two very productive terms, but I have always been about grassroots activism. I do think that a lot of people think I’m a thoughtful critic and that I try to be constructive. I mean, there are times that I haven’t been constructive because sometimes it’s just easier to vent, but sometimes you have to get people’s attention. I just hope that I fostered the sense that West Hollywood can always be a participatory democracy. Public participation is the yeast that makes the dough rise, but it’s also the ballast that keeps the ship righted. I’ve been involved in enough different campaigns and different causes in West Hollywood to see that people can make a difference. You don’t have to sit back and say, “Oh gee, I don’t have any power.” You have to allow yourself to be empowered.